I started out in computer vision in 2004. I was walking along the corridors of the computer science department at the University of Adelaide (in South Australia) looking at notices put up by lecturers advertising potential undergraduate thesis topics. There wasn’t much there for me until one particular topic caught my eye: developing a vision system for a soccer-playing robot.

Well, the nerd in my awoke! I knocked on the lecturer’s door and 5 minutes later I walked out with a thesis topic and one of those cheeky smiles that said “we’re in for a lot of fun here”. Little did I know that my topic choice was to be the beginning of my adventures in computer vision that would lead me to a PhD and working for companies in Europe and Australia in this field.

So, I’ve been around the world of computer vision for nearly 15 years. When I started out, computer vision was predominantly a research-based field that rarely ventured outside those university corridors and lecture theatres that I used to saunter around. You just couldn’t do anything practical with it – mainly because machines were too slow and memory sizes were too small.

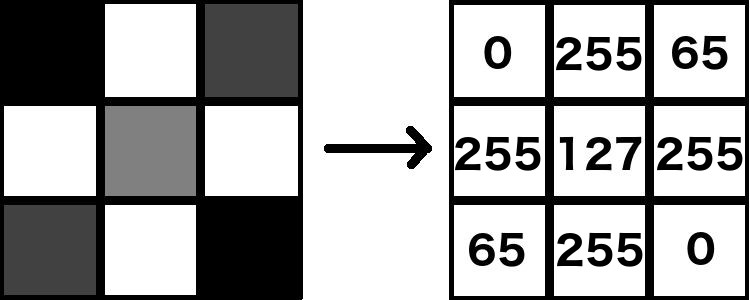

(Note: see this earlier post of mine that discusses why image processing is such a computation and memory demanding activity)

But things have changed since those days. Computer vision has grown immensely and most importantly it’s shaping up to be a viable source of income in the industry. It’s truly been a pleasure to witness this transformation. And it seems as though things are only going to get better.

In this post, then, I would like to present to you how much computer vision in the industry has grown over the last few years and whether this growth will continue in the future. I would also like to briefly talk about what this means for us computer vision enthusiasts in terms of jobs and opportunities in the workforce (where I am based now).

(Note: in my next post I write in more detail about the reasons behind this growth)

Computer vision in the last few years

Recently, growth in computer vision in the industry has surged. To understand just how much, all one has to do is analyse the speed at which top tech corporations are moving into the field now.

Apple, for example, in this respect made at least two significant takeovers last year, both for an undisclosed amount: one of an Israeli-based startup in February 2017 called Realface that works on facial recognition technology for the authentication of users (could it be behind FaceID?); and another in September of 2017 when it acquired Regaind, a startup from Paris that focuses on AI-driven photo and facial analysis.

Facebook has joined the game also. Two months ago (Nov, 2017) it bought out a German computer vision startup called Fayteq. Fayteq develops plugins for various applications that allow you to add or remove objects from existing videos. Its acquisition follows the purchase of Source3, a company that develops video piracy detection algorithms, which also took place in 2017.

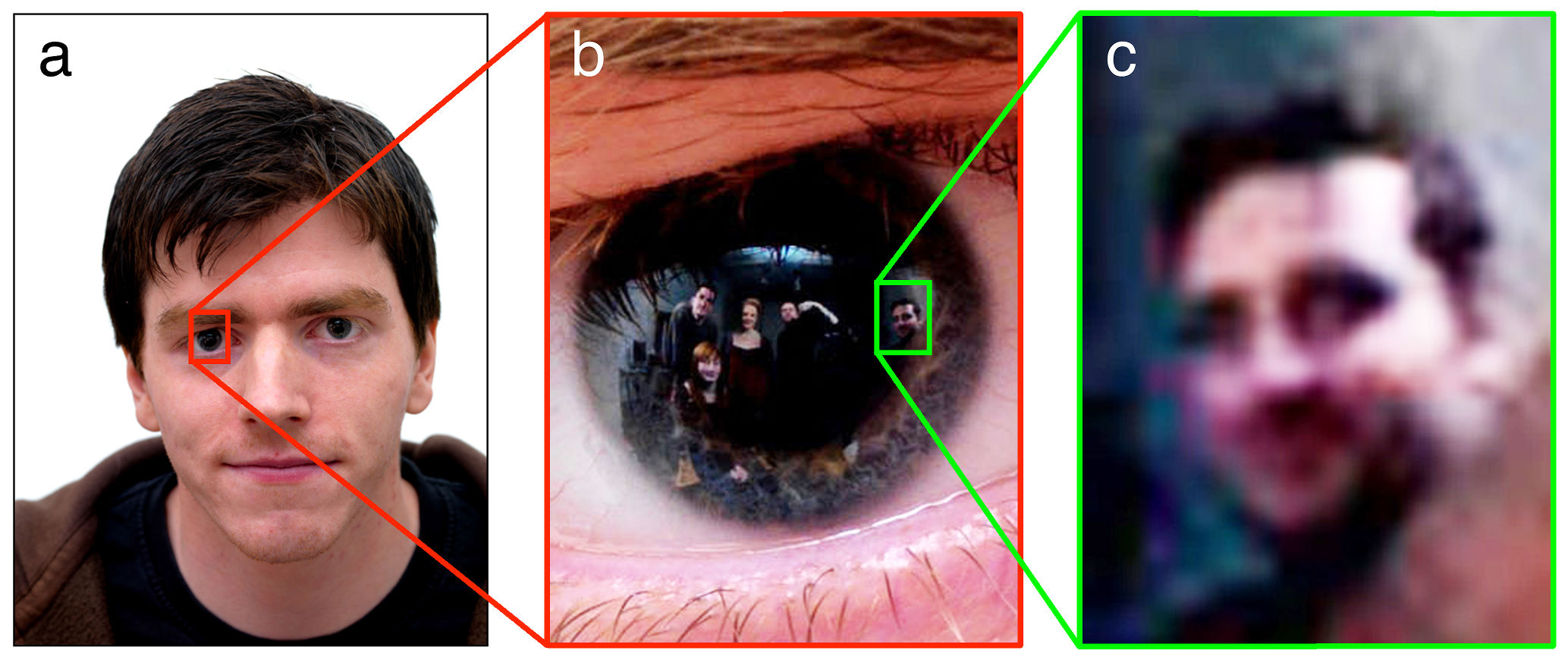

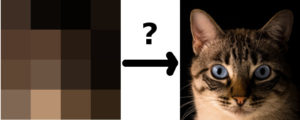

While on the topic of social media, let’s take a look at the recent moves made by Twitter and Snapchat. In 2016 Twitter bought Magic Pony Technology for $150 million. Magic Pony Technology employs machine learning to improve low-quality videos on-the-fly by detecting patterns and textures over time. Whereas Snapchat, also in 2016, acquired Seene, which allows you to, among other things, take 3D shots of objects (e.g. 3D selfies) and insert them into videos. Take a look at what Seene can do in this neat little demo video. Apologies for the digression but it’s just too good not to share here:

Amazon has noted the growth of computer vision in the industry so much so that it recently (Oct 2017) created an AI research hub in Germany that focuses on computer vision. This follows shortly upon its acquisition of a 3D body model startup for around $70 million.

The clear stand-out takeover, however, was made by Intel. Last year in March it bought out Mobileye for a WHOPPING $15.3 billion. Mobileye, an Israeli-based company, explores vision-based technologies for autonomous cars. In fact, Intel and Mobileye unveiled their first autonomous car just three days ago!

Other notable recent acquisitions were made by Baidu (info here) and Ebay (info here).

Such corporate activity is unprecedented for computer vision.

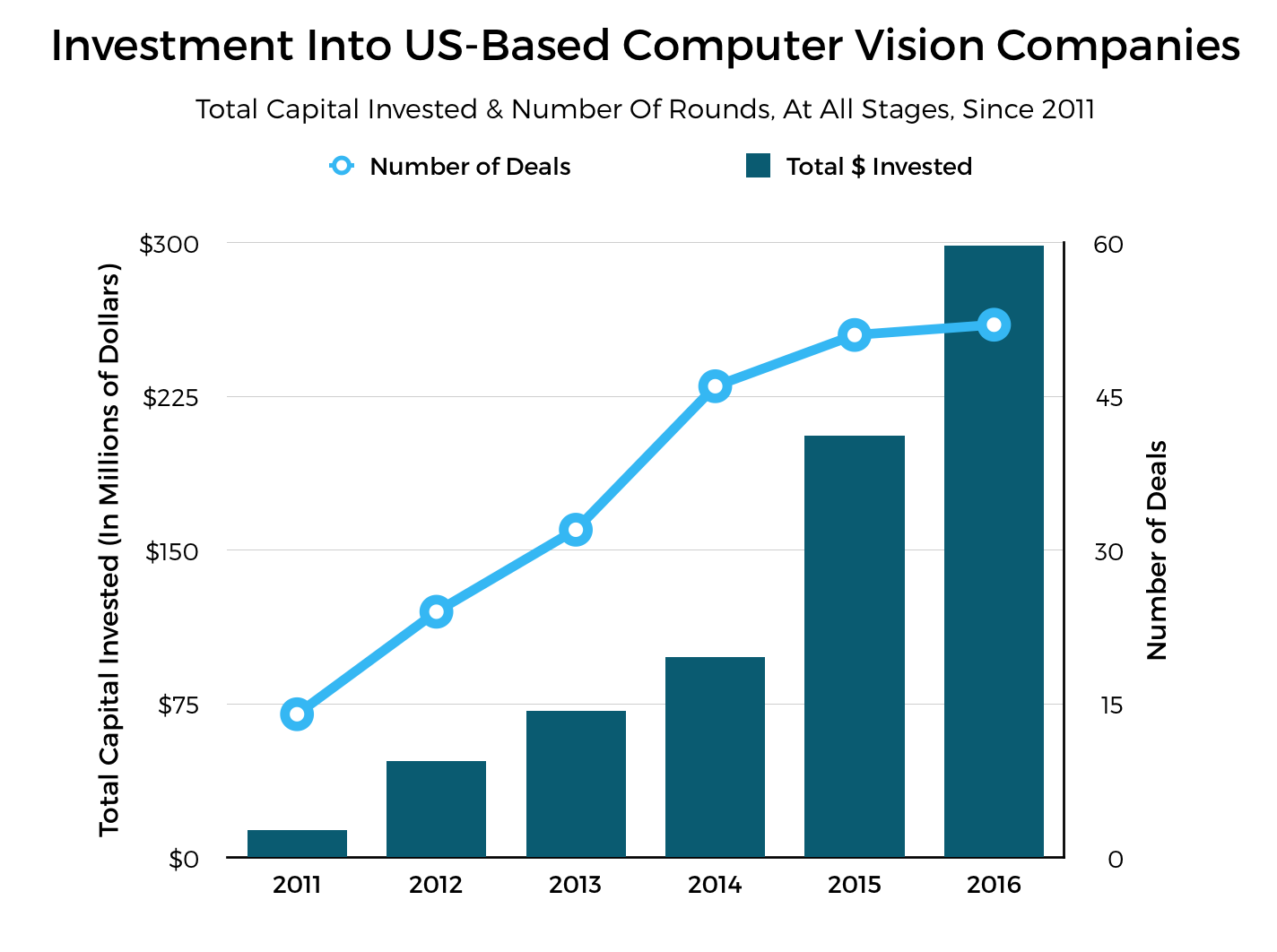

Let’s try to visualise this growth by looking at the following graph (from 2016), showing investments into solely US-based computer vision companies since 2011:

A clear upward trend can be seen beginning with 2011 when investments were barely above zero. In 2004, when I joined the computer vision club, it would have been even less than that. Amazing isn’t it? Like I said, back then the field very rarely ventured outside of academia. Just compare that with the money being pumped into it now.

Here are some more numbers, this time from venture capital funding:

- In 2015, global venture capital funding in computer vision reached US$186 million.

- In 2016, that jumped three-fold to $555 million (source).

- Last year, according to index.co, investments jumped three-fold again to reach a super cool US$1.7 billion.

The stand-out from venture capital funding from 2017 was the raising of $460 million from multiple investors for Megvii, a Chinese start-up that develops facial recognition technology (it is behind Face++, a product I hope to write about soon).

Serious, serious money, we’re talking about here.

What the Future Holds for Businesses and Us

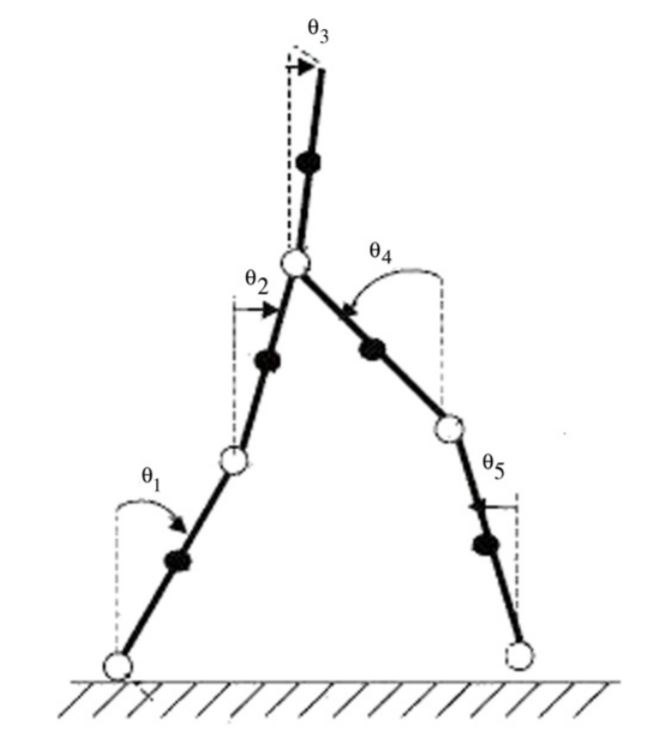

Undoubtedly, further growth can be easily predicted for computer vision in the industry. Autonomous cars, commercialisation of drones, emotion detection, face recognition, security and surveillance – these are all areas that will be driving the demand for computer vision solutions for businesses.

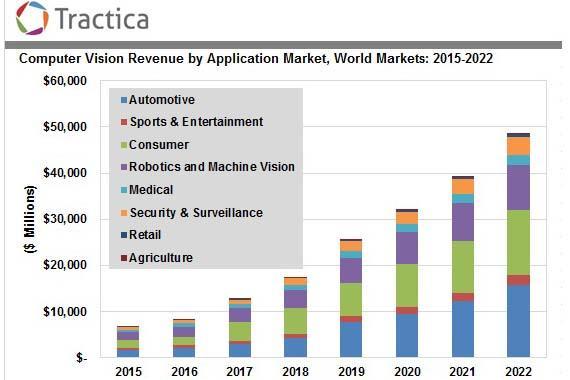

Tractica predicts that the market for these solutions will grow to $48.6 billion by 2022. Autonomous cars and robotics will be the major players in these future markets:

What does this mean for us computer vision enthusiasts? Will it be any easier to find those elusive jobs?

In my opinion the state of affairs at our level will not change for a while. A high-level of technical knowledge and understanding backed up by a PhD degree is still going to be the norm for some time to come. Like I mentioned in a previous post, you will need to branch out into other areas of AI to have a decent chance of working on computer vision projects.

Having said that, the situation will slowly start to change once businesses and governments come to realise just some of the things that can be done with the data being acquired by their cameras (more on this in a future post). It’s only a matter of time before this happens, in my opinion, so it’s worth sticking with CV and getting ahead of the crowd now. Investing your time and effort into CV will certainly pay off dividends in the future.

Summary

In this post I presented how much computer vision has grown over the last few years. I looked at some of the recent acquisitions into CV made by big companies such as Apple, Intel and Facebook. I then reviewed the current investments being made into CV and showed that this area is experiencing unprecedented growth. Before 2010, computer vision rarely ventured outside of academia. Now, it is starting to be a viable source of income for businesses around the world. Having said that, the situation for us computer vision enthusiasts will not change for a while. CV jobs will still be elusive. More businesses and governments need to realise that the data being acquired by their cameras can also be mined for information before the effects of this unprecedented growth in CV start to significantly affect us. Thankfully, in my opinion, it’s only a matter of time until this happens so it’s worth sticking with CV and getting ahead of the crowd.

To be informed when new content like this is posted, subscribe to the mailing list (or subscribe to my YouTube channel!):